E-Mu Reborn? Rossum Electro-Music

In the fourth and last part of our interview with Dave Rossum he tells us about the last phase of the E-mu history and about his plans for the future…

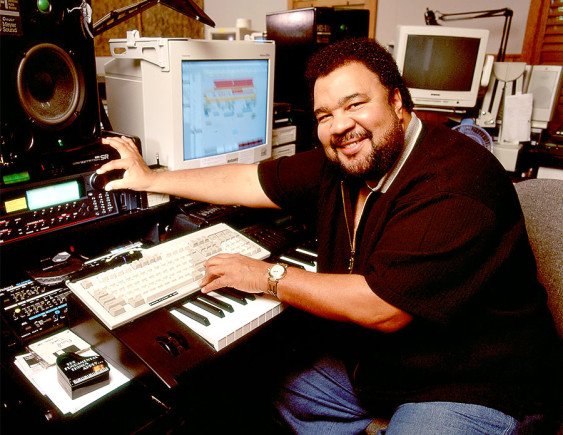

Left to right, Marco Alpert, Scott Wedge, me, and Ed Rudnick at E-mu’s 30th anniversary party in 2002.

A few facts about this foto:

We were the four central people of E-mu Systems. Me, of course, you know. Scott Wedge was E-mu’s co-founder, as described in the interview. When E-mu was acquired by Creative, Scott stepped down as CEO (Creative didn’t need a CEO), and has been „gainfully unemployed“ since. He’s tinkered a bit on an invention for aircraft communications audio, but never got back into industry.

Marco Alpert began working with E-mu in 1976, and was E-mu’s VP of Marketing for many years. He left E-mu in 1994 to join Akai as a strategic marketing consultant. For the past 17 years, he was Vice President of Marketing at Antares, a job he left in November 2014.

Ed Rudnick was E-mu’s first employee, joining us in April 1973. He had stints as Chief Technician, VP of Manufacturing, and head of QA. Ed succumbed to cancer in 2008, and we all deeply miss him.

Peter:

It was pretty obvious that the synthesizers with many faders and knobs became attractive again for musicians. And of course also the analog-sound. You started your career with modular synthesizers. Have you never planned to build a modern analog synthesizer instead of releasing one after another Proteus?

Dave:

I have always understood that musicians relate to their instruments physically, and that knobs, switches, and even patch cords are part of that relationship. For me, even the feel of the knobs was critical. In the E-mu modular, for example, I insisted our knobs be machined aluminum rather than the plastic used by Moog and others. But cost drives price, price drives volume, volume drives profitability. Knobs, switches, and jacks are the most expensive part of modular music synthesizers. They (and analog circuitry too) don’t follow “Moore’s law” and get cheaper every year the way digital electronics does.

Peter:

In contrast to other big names as Moog, Arp, Sequential Circuits or Oberheim you digressed from analog synthesizers at the beginning of the 80s. Why?

Dave:

In the early 1980’s, the modular synthesizer seemed dead – our modular sales had dropped to essentially zero. We sold off all our stock, and never looked back. And the marketplace agreed with us, at least until the mid-2000’s. While there certainly were people (including me) who bemoaned the lack of analog warmth in the digital synths, and missed the array of knobs to control things, and the ability to patch with a cable instead of a mouse, nobody was willing to consider paying the price until very recently. Also, under Creative, E-mu became more risk averse. In the mid ‘90’s, Creative was willing to fund risky projects like Darwin and Ivy. But as 2000 approached, E-mu needed to stick to programs that were sure to come near to break-even, and even then analog synths were unproven in the market.

Peter:

E-mu tried with the DARWIN to establish them in the HD-recording. How come and did you succeed?

Dave:

With Creative to back us, E-mu tried to expand our marketplace from synthesizers to the broader semi-pro music market. We had a vision of the digital music studio, with instruments, recorders and mixer consoles all seamlessly integrated. The only product from these initiatives that made it to the marketplace was Darwin. Creative funded a custom chip for Darwin, and helped us license certain technologies that we couldn’t develop in house in a timely manner. The other project, a mixer console code-named Ivy, was never released. Unfortunately, Darwin turned out to be too little, too late. By the time it shipped, there were several more well developed alternatives, and pure software solutions were just becoming feasible. Darwin would have been a great product, but the initial release was missing a few key features, had a few bugs, and missed the mark in some places in its user interface. We had plans to fix all this, but without getting significant initial revenue and a user base, they never came to fruition.

Peter:

What should they have done better at Darwin?

Dave:

Internally, Darwin was the first project where I observed a big failure in communication between marketing and engineering at E-mu. The engineers worked long and hard to make Darwin everything they felt it needed to be, but when the first product was ready, marketing said it wasn’t sellable – key features were missing. This was a surprise to everybody; it seemed that marketing thought the missing features would be part of the initial release, while engineering said they couldn’t to everything, so they did the key features that they’d been told were needed. This was very hard on morale. Ivy was even worse – after much engineering effort, it was cancelled before ever being announced to the marketplace.

Peter:

When AKAI released their S5000 and S6000 with the high number of Bugs you countered with the EMU IV Ultra series. Did you get the feeling that AKAI lost ground and E-mu established themselves in the studios around the world?

Dave:

Akai definitely lost ground to E-mu in that era, but I honestly don’t know how much the EIV had to do with that. The EIV Ultra began as a “complete re-design” of the EIV, but since the effort to re-write the software from the ground up would be too expensive, and the G-chip II sound engine was still unequalled by rivals, we chose instead to just upgrade the processor and incrementally improve the software. I’m sure these decisions minimized bugs; the resulting product was also both reliable and powerful. The EIV Ultra is still being used in studios worldwide today.

Peter:

In an audio test we compared the EmuIIIXP with the Emulator IV. Everybody agreed that the sound of the EmuIIIXP was warmer and a bit more analog than the sound of the Emulator IV.

Dave:

Sound is subtle, and any real „scientific“ tests must be carefully done in a „double-blind“ way, so the listeners cannot possible gain even the most subtle cues as to which sound is which.

The filter chips in the EIIIXP and EIV are both H-chips, so the mathematics of the filter DSP are identical to the last detail. However, I can think of two possible ways they could differ.

First, the programming of the H-chip could be different. Each filter had a total of 8 16-bit coefficients, and these could be programmed differently for the two synths. Any difference would affect the sound. Since I don’t have access to the source code for either synth, it would be very difficult to know if the coefficients were the same or not.

Also, the EIIIXP used the original 32 voice G-chip, while the EIV used the 128 voice configuration of two G-chip IIs. The mathematics used by the G-chip and the G-chip II for sample interpolation (pitch-shifting) were very similar, but not identical. The G-chip II was slightly brighter in its most common configuration. This is actually a more accurate representation of the original sample, but it could give the sound a less warm feeling.

Peter:

You were one of the first to create a virtual analog synthesizer. Did you share your knowledge with others?

Dave:

The EMAX II was the first E-mu product to use the „H-chip“, our digital filter chip. The intent of the chip was to make digital filters sound „analog,“ and obviously we succeeded. There’s actually a technical paper by me with that title – „Making Digital Filters Sound Analog.“ It’s online if you google it.

Peter:

And then I’m wondering that both AKAI and E-mu didn’t have anything to come up with against the first software-samplers like the EMAGICS EXS-24 or STEINBERGS HALION. As a big fan of E-mu I’ve been waiting for the first plug-in version of the emulator. What happened?

Dave:

As early as the late 1980’s, Scott Wedge and I envisioned the underlying technology of hard-disk based samplers. In retrospect, we probably should have patented those early ideas, even though they couldn’t be used in an affordable instrument at that time. Back then, of course we had been thinking of building keyboards or modules, not computer software. Nonetheless, had we protected our ideas, we might have established a position from which we could have entered the software market effectively. At various times, E-mu considered seriously pursuing software products. But the structure of software companies is radically different from hardware companies. Hardware companies have purchasing, PCB and mechanical engineering, inventory management and production departments that are virtually absent in software companies. It’s very rare for a hardware company to become cost-efficient producing software products. At the time, E-mu was struggling to become consistently profitable, and incapable of making the radical changes that would allow us to effectively compete with the lean software synthesizer companies.

E-mu did create the Emulator X. It’s a very nice software product, but was originally released bundled with the E-mu branded sound cards and I/O modules. When released stand-alone, it wasn’t competitively priced. All this is really because we weren’t structured to be a software company.

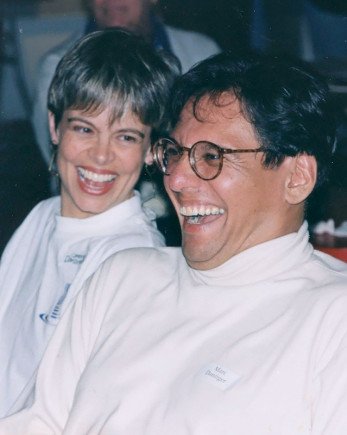

Further information about this foto:

One of the UCSC muons of the summer of 1971 – Marc Danziger with his wife, taken at the 25th anniversary celebration. Marc built the cabinet for the E-mu 25, and did a lot of other mechanical and graphics stuff for the prototype. He is now a technology strategist in Los Angeles.

Peter:

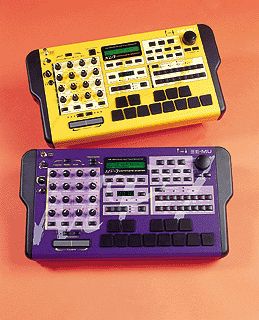

Also we waited for an official follow-up on the EMU SP-1200. Instead you put the Proteus in a Desktop-Unit and called it MP-7 and XL-7. Did E-mu run out of innovations and ideas?

Dave:

The success of the SP-1200, and the arc of its various successors, have always surprised us. The SP12 was derived from the Drumulator – and though the samples were 12 bit, it used “drop-sample” pitch shifting which creates substantial distortion. But amazingly, that distortion proved musically useful. The SP-1200 simply added my floppy disk interface, hitting a market opportunity at just the right time. My work then turned to chip development – designing chips for high fidelity pitch shifting and complex but analog-sounding digital filters. Other engineers took over most of the rest of product design. Our next product in the percussion arena was Procussion – a redesigned Proteus engine with software and a user interface for use with sequencers and drum pads. Like many E-mu products, the capabilities were great, but the effort to learn and use them effectively was high. While Procussion still has a small but devoted following, it never took off like the SP-1200. It’s a sound module, not a drum machine.

By the mid-90’s, E-mu’s vision was the digital music studio. While we maintained the Emulator and Proteus families, the lackluster response to Procussion led us to ignore the drum machine market entirely. The Emulator family was flexible enough that it could be programmed as an excellent percussion module, and that seemed enough. The Emulator and Proteus family ultimately evolved to the Proteus 2000 engine.

The MP-7 and XL-7 were just desktop versions of that same sound engine. Since at this time, I was not very involved in E-mu’s decision making, I honestly don’t know if when these products were designed, any consideration was given to adapting the sounds and software to build on the SP-1200 legacy. I doubt we had anyone on staff that had a real understanding of what made the SP-1200 legendary. I would not say that E-mu ever ran out of innovation and new ideas. The changes were much more subtle than that; even in retrospect it’s difficult to sort out why E-mu failed to thrive after the Creative acquisition.

Peter:

In the end you sold E-mu to CREATIVE LABS and ENSONIQ. Every musician was shocked. Why did you sell E-mu?

Dave:

After the challenges of the Emulator III and getting the Proteus into manufacturing, we realized unless we made changes, E-mu’s existence would be forever at risk. In 1990, we hired Charlie Askanas, a former E-mu board member and experienced CEO, to lead us. The computer multi-media revolution was just beginning, and we knew the G-chip technology would work ideally for sound cards. We didn’t have the capital to attack that market ourselves, so we were very excited in 1992 when Creative, the market leader, made a deal to license the Proteus technology in the form of the Wave Blaster.

We often said what E-mu needed was “parentage” – investors, or a partner company, with deep pockets that could help us both in business and finance. We had thought about going public, but Wall Street remembered Kurzweil Music and was not interested.

In December of 1992, Charlie called Scott and me into his office. He had received a call from Creative asking if we were interested in talking about acquisition. Charlie told Scott and me that if E-mu were sold, Creative would “take this place apart like a Christmas turkey” and we would be “the two least popular guys in Santa Cruz.” On the other hand, Creative’s business was booming, and we had been looking for parentage without success. Should he blow them off, or meet with them? We decided there was nothing to lose by at least listening to what they had to say.

Charlie came back with a big grin. He said that Creative opened the meeting by saying they wanted to E-mu to continue unchanged in the music business, giving us the backing to thrive. The reason for acquisition was so they could be certain to benefit from E-mu’s technological advances. As we probed further, Creative’s founders seemed sincere in this belief, and we learned that Mr. Sim, the CEO, had a passion for music.

So we decided to go for it. Every E-mu employee at that time was a company stockholder, so everybody got a very nice bonus. And Creative was, for many years, absolutely true to their promise. I became first the director of the “Joint E-mu/Creative Technology Center” (now called the “Advanced Technology Center”, or ATC), and later Creative’s Chief Scientist. Sim has said many times that E-mu was the best acquisition Creative ever made.

Peter:

This sounds plausible. But yet we had the feeling that E-mu has lost a bit of its glamour then…

Dave:

I would not say that E-mu ever ran out of innovation and new ideas. The changes were much more subtle than that; even in retrospect it’s difficult to sort out why E-mu failed to thrive after the Creative acquisition. It may have been simply due to the dynamics of various personalities. Through 1993, Scott Wedge, Marco Alpert, Ed Rudnick and I were directly very involved with virtually every product, and we had developed together a team dynamic that worked extremely well. After the acquisition, Scott and Marco both left, Ed moved into software quality management, and I focused more on technology development that could be used by both Creative and E-mu.

Marco Alpert, our visionary VP of Marketing, was recruited away from us just after the Creative acquisition. Though we had other marketing folks, none equaled Marco’s skill in teaming with engineering to create innovative product concepts. On the engineering side, nobody stepped up to take the music product leadership role that I had abandoned to lead the Tech Center. As a result, engineering was disconnected from marketing and sales – they no longer shared a vision. I also sometimes wonder if being constantly at risk wasn’t what made E-mu work – in our heyday we all knew our security depended on doing everything right, every time. But though I was disappointed that E-mu wasn’t thriving, I also felt like it was not my place to step in and save it. My child had grown up, and needed to learn to make it on its own. Honestly, I might be that the marketplace just got more competitive, particularly with the move towards software products, and we wouldn’t have done any better no matter what.

Peter:

As far as I unterstood, you didn’t work directly for E-mu then?

Dave:

Even though Creative was highly supportive of E-mu within the music industry, there were undercurrents of resentment toward Creative within E-mu, and sometimes these were counter-productive. I’ll give an example.

In the early 90’s, we developed a 16 bit effects engine for our products, based on an Analog Devices 2105 DSP chip. Because it was 16 bit, its fidelity was limited. At the same time, I was developing the EMU8000 chip for Creative’s sound cards, which included a custom 24 bit effects engine. Internally, the EMU8000 was called the “G0.5” because it used a cost reduced G-chip algorithm for pitch shifting. The EMU8000 cost almost nothing, due to Creative’s volume, and I had carefully designed it so E-mu could bypass the sampler and use just the effects engine with our G and H chips. But I encountered huge resistance to using a “cheap” Creative chip in E-mu’s products. Finally, somebody put together a double-blind test and everybody overwhelmingly agreed the EMU8000 sounded much better than the 2105. But we delayed 2 years in making that improvement simply because a few decision makers thought “Creative” meant inferior sound quality.

Peter:

In 1998, Creative purchased also Ensoniq, right?

Dave:

Creative’s purchase of Ensoniq in 1998 is quite a different story, and really has nothing to do with the music marketplace. As Microsoft promoted “plug-and-play” technology, they forced the Sound Blaster standard that had made Creative successful into obsolescence. In a big meeting, the top Creative engineers discussed what could be done. I asked the Singapore based software team, “Are you absolutely certain there isn’t some clever hardware/software trick that could be used to get around Microsoft’s requirements?” I was told no, they had proved this was impossible, and, to my eventual shame, I didn’t make any effort to dig deeper.

Ensoniq’s engineers figured out that clever trick, and as a result were able to make a sound card that was very competitive with the Sound Blaster. Creative’s response was to buy Ensoniq, and as Chief Scientist I helped pave the way for that acquisition. We all (Creative’s executives, E-mu folks, and most of Ensoniq’s engineers) hoped that Ensoniq technologies, products, and talent could benefit E-mu. But for various reasons, we were never able to effectively use what Creative had purchased.

Peter:

What is your personal career progress within E-mu and when did you leave the company for good?

Dave:

For many years, I was excited and delighted working with Creative. They smoothed out our financial ups and downs, funded development of many projects, from Morpheus and EIV through Darwin and Proteus 2000, and were very supportive about E-mu’s prospects. I was involved in chip development, both for Creative and for E-mu. Our digital VLSI designers developed chips for Darwin and a wonderful effects engine for E-mu synthesizers. We were also doing cutting edge research at the Tech Center into really interesting advanced music synthesis techniques. Things were very promising.

But sadly, E-mu was not thriving. The digital music studio project failed. While the sound modules continued to sell, nothing took off like the original Proteus. It seemed like the wonderful rapport between engineering and marketing that fueled E-mu in the 80’s and early 90’s just wasn’t there anymore.

In 2001, Sim asked for my support. E-mu had been losing money – though not a lot – consistently since the acquisition. Creative was no longer booming; he was under pressure from his board to make broad cuts. Sim felt his board would insist on shutting E-mu down. He proposed giving E-mu a choice – either decide to stay primarily in the music market and become profitable or die, or move to the computer peripheral market. He convinced his board that if E-mu did that, the technology spin-offs to Creative would cover any losses.

I supported this proposal. I felt that Creative had more than honored their word to E-mu. Now they needed us to stop losing money – we could make a responsible choice. In the end, we muons chose the safe path, moving into computers, though ultimately that wasn’t profitable either.

It’s hard to describe exactly how I feel about it all. Creative supported E-mu beyond any expectations. Sometimes in my dreams I feel like I abandoned E-mu, but I don’t feel so in my waking hours. We always knew music is a tough market – “your customers are always broke.” I’m certainly sad that E-mu didn’t survive. But I’m not sure that if E-mu had survived, it would still be the E-mu I created and loved. I’ve said a lot about E-mu’s profitability, but for all of us, music was the focus. Profitability was just what we needed to make more music tomorrow.

Peter:

What do you think about E-mu’s progress since the takeover of CREATIVE LABS? Aren’t you sad about that?

Dave:

As I mentioned, after the Creative acquisition, I first directed the Tech Center, then became Creative’s Chief Scientist. That position involved a lot of education (I would teach Creative’s engineers in Singapore about everything from circuit theory to DSP), technology evaluation, and public speaking. In 1999, with my son in high school, I chose to “semi-retire,” cutting my hours back to about half-time. I stayed in this mode until about 2007, when Creative asked me to once again be involved in chip development at ATC.

My good friend Dana Massie, who started at E-mu in 1983 and was responsible for many E-mu DSP innovations, had been trying to recruit me to join him at a Silicon Valley start-up, Audience Inc. In 2011, Creative finally had to pull the plug on E-mu. This was particularly hard on me because it was the only time Creative took an action involving E-mu without discussing it with me first. So I decided I no longer owed them my loyalty, and took the job at Audience. I became Sr. Director of Architecture, and got to work with Dana and many other former E-mu and Creative ATC employees again. While it was fun working on mobile phone audio chips, in 2014, I began to realize how much I missed the music industry. I reluctantly left Audience in early 2015.

Peter:

E-mu is still a well-known brand name. Even with all the efforts CREATIVE LAB is putting in there, E-mu will never represent soundcards. It’s still well known for their outstanding sampler, synthesizer and drum computers. These days many brands are getting revitalized. Dave Smith shows everyone right now how that works. Could you imagine revitalizing E-mu? Even though the company wouldn’t be called E-mu anymore – maybe something like DAVE ROSSUM INSTRUMENTS? What do you think about that idea?

Dave:

I think my friend Dave Smith might not like that particular name choice! But in fact, I can now announce that I’m starting, with Marco Alpert, a new company: Rossum Electro-Music. I don’t think I’ve got the energy or time to completely rebuild E-mu, but we’ll have some fun and hopefully make some nice products.

Peter:

What are your plans of Rossum Electro-Music? Hardware, Software… digital or analog, and when can we expect the first Rossum Electro Products?

Dave:

Rossum Electro-Music will carry on the classic E-mu tradition to create powerful (and fun-to-use!) musical hardware. So there’ll be interesting analog technology, some real innovations in the digital domain, and, of course, a focus quality construction and reliability. Our first products, which you’ll be hearing more about this winter, will be unique entries in the exploding Eurorack synthesizer market. While they build upon ideas that we pioneered at E-mu, they take advantage of current tech to offer a whole new range of creative capabilities. We’re really excited about what we’re working on and have high hopes that the Eurorack folks will share that excitement. Farther down the line, well, we’ll just have to see… For now, I’m just having a ton of fun doing this.

Peter:

Are you already retired? What are you up to these days?

Dave:

After leaving Audience earlier this year, I joined Universal Audio in Scotts Valley as a Technical Fellow. UA, like Audience, employs a number of ex-muons, as well as many other colleagues from years past. It’s great fun working with all of them. Furthermore, UA is investing in Rossum Electro, so I’m splitting my time between the two. I don’t know that I’ll ever retire. Technology and music are in my blood, and I’m still having lots of fun on the job. Maybe I’ll even get a shot at changing the way the world makes music once again!

Peter:

Dave, thank you so much for that interview! Thanks for the extraordinary and exciting insight of the history of E-mu!!!