How to become an Emu

DAVE ROSSUM

It is not that easy to write an introduction for this interview, that copes with Dave Rossum. He absolutely has to be mentioned in the same gasp as synthesizer-pioneers like Bob Moog or Dave Smith.

Thanks to Amazona.de you have the chance to follow Dave’s journey through time within the next 4 weeks and get some very interesting and personal insights to his life.

Yours

Peter Grandl / June 2015

Part 1: From biology to modular system

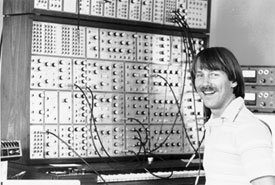

Dave Rossum (*1949) in his studio on 28th April 2015. His sunburn came from running the Big Sur marathon (4:47:19 – 14th place in his age group.

Peter:

Hi Dave. Let’s start at the beginning. Scott Wedge and you started 1970 with constructing a modular Synthesizer. How did you get the idea for that?

Dave:

I was an undergraduate studying biology at Caltech in 1969, when some friends decided to form a music group just for fun. One of them, Robert Land, said his dream was to play the synthesizer, but first we had to build one. Our friend Steve Gabriel, a EE major, took the lead on that project.

In the fall of 1970, I began graduate work at UC Santa Cruz, where my advisor, Harry Noller, invited me to join him in the music department where the students were unpacking their new Moog Model 12. Something clicked – by that evening, I was the one teaching them about the synthesizer. I invited my Caltech friends to come see the UCSC Moog in November of 1970, and in late December, I returned to Caltech to visit them. That was when E-mu Systems was born, and we made our first progress in building a real synthesizer. We continued to work together, with me driving down to Caltech when my studies allowed, through the spring of 1971. Over the summer of 1971, the Caltech guys came up to Santa Cruz, where we built our first competent synthesizer, the E-mu 25, a self-contained unit similar in scope and concept to the ARP 2600.

In August of 1971, my high school friend Scott Wedge visited us in Santa Cruz. He, too, caught the synthesizer bug. It was Scott and I that decided that a modular system was what we really wanted to build.

Dave was taking time off the Sierra teaching rock climbing, while the rest of the folks tried to figure out how to build a stable oscillator. (1971)

Peter:

You were still studying when you started with its construction. Did you actually plan on making a living with the synthesizers or was it just a hobby?

Dave:

When we began designing the synthesizer at Caltech, it was purely for fun. But early in 1971, one of the Caltech guys, Jim Ketcham, heard that there was a request for bid from the San Diego School District for music synthesizers to add to their high school music program. We decided to build a prototype and try to get the bid – if we won, we’d start a business. The prototype we built, which we called the „Black Mariah,“ wasn’t all that good a synthesizer – after all, this was our first attempt. We were never seriously considered by San Diego, and eventually we pushed the Black Mariah out the Dabney House library window.

I had a modest inheritance from my grandmother, about $3,000, and decided that I would use this to bankroll our summer 1971 project to build the E-mu 25.

There were six of us then: myself, my girlfriend Paula Butler, two UCSC friends (Marc Danziger and Mark Nilsen), and Jim and Steve from Caltech. Our goal for the summer was to build a saleable prototype E-mu 25, and then we’d consider starting a formal business. At the end of the summer, we had succeeded in building the synthesizer, but the Caltech guys decided to complete their education, and Marc and Mark chose to pursue other careers. The Caltech guys took possession of the first prototype E-mu 25, and Scott (who had just joined me), Paula and I were left to pursure E-mu Systems as a business.

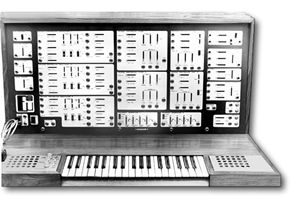

A dream of a Modular System with aluminium-potis.

The E-MU System, a special edition with transparent covers.

Paula got a job at American Microsystems (AMI), Scott went back to school at UC Berkeley, and I began working with some Caltech classmates at a semiconductor test startup called Santa Clara Systems. My deal with SCS was that I would work for a very modest salary, but I could use all their equipment and lab supplies after hours to work on synthesizers.

We re-designed the E-mu 25, sold the second prototype, and then started work on the E-mu Modular System, which we announced in the fall of 1972. On November 27, 1972, E-mu officially became a business. We didn’t know if it could support us – I still worked at SCS, Scott had dropped out of UC, but was living with his mother and had no living expenses, and Paula had a good job at AMI to keep us all fed. We had high hopes for E-mu Systems.

Peter:

In 1972 you founded your first company called E-Mu. What‘s the story behind that name?

Dave:

The name „Eµ Systems“ was born at Caltech on December 29, 1970. The Greek letter µ (pronounced „mu“) is the symbol for „micro“, so the name was simply the first syllables of Electronic Music, but had the connotation of miniaturization as well. Though we didn’t become a legal company until 1972, we used the name to purchase parts, and outside our abode in the summer of 1971, a sign read „Eµ Systems – Starships and Synthesizers since 1984.“ Throughout the 1970s, we continued to spell the company name with the Greek letter. But in 1979, when we incorporated, we learned that the law in California required that the corporation name be spelled with only Roman alphabet characters, thus the change to „E-mu Systems.“ About that time, we adopted the Australian bird as our mascot.

Peter:

Your first product was a polyphone keyboard, wasn’t it? What did you move from producing synthesizers to polyphone keyboards?

Dave:

The Moog synthesizer keyboard only played the lowest key depressed; the ARP keyboard would play the lowest and highest notes. As we began to design the E-mu Modular Synthesizer, it was clear that musicians wanted a polyphonic synthesizer, but at that time nobody had ever produced one. So I was working on solving that from the early days.

In 1973, I built a prototype digital polyphonic keyboard out of TTL logic. It consumed a couple Amps of power, but our growing modular synthesizer now could play four notes at once. I re-designed the circuitry to use CMOS logic, and created the E-mu 4050 Modular Keyboard product. We showed it to potential customers, and sold the first one to Leon Russell in 1975. The 4050 could be configured to operate as a monophonic keyboard (low note only) or a polyphonic keyboard up to 10 voices.

When 8 bit microprocessors became available, we quickly realized that the polyphonic keyboard was an ideal task for them. The 4060 Microprocessor Keyboard was introduced in 1977. It supported up to 16 voices and included a polyphonic sequencer. Scott Wedge did the programming; I designed the hardware. Both the 4050 and 4060 were designed specifically for use with the E-mu Modular System.

Peter:

Different manufacturer used that licensed keyboard idea in their production. We’re talking about big names like Oberheim with their „Four Voice“ and Sequential with the famous „Prophet 5“. What was the unique thing about that new keyboard?

Dave:

I met Tom Oberheim at the Los Angeles AES show in 1974, and we quickly became good friends. Once, over lunch, he told me that he was having problems matching the FETs in his phase shifter; he was sure there was a way to replace them with CA3080s, but he hadn’t been able to figure out how. I dashed out a schematic on a napkin, and he asked „Did you just invent that?“ I replied I did. He asked if I thought it was patentable, and I agreed it was. We ended up filing for a patent (which also covered the SSM2040) with me as inventor, Oberheim Electronics as the patent owner, and a license back to me for all other rights.

When Tom saw the TTL prototype polyphonic keyboard, we arranged another patent along the same lines. What made our polyphonic keyboard unique was that we chose to make the logic so that rather than assign voices by lowest and highest note, we assigned them by first played, second played, etc. We were the first to market with a solution that actually worked. We also had logic for when you played the same note over and over again: it would assign it to the same voice, eliminating an annoying cycling variation in the sound due to the inevitable slight variations in the analog synthesizer voices.

Tom used the circuitry from the 4050 design for the Oberheim Four Voice, and later we licensed the 4060 technology to Sequential Circuits, which ran on the Z-80 processor in the Prophet. If fact, Dave Smith developed the original software for the Prophet 5 on the same Z-80 development system we built at E-mu for the 4060 project.

Peter:

E-Mu grew rapidly. Where did you have your production located in the beginning?

Dave:

In the early days, E-mu was just located wherever I lived – in my dorm room at UCSC, the house we rented at 625 Water Street during the summer of 1971, and spare bedrooms at other houses. The first official location of E-mu, our address when we became official, was 3455 Homestead Rd, #59, in Santa Clara. This was a unit in „The Diplomat Apartments,“ but we always wrote the address as „#59,“ or even „Suite 59“ to give the illusion we were in a business building. Still, this was where Leon Russell, with his synth programmer Roger Linn, came to get a demo of the E-mu Modular. We build the modules and submodules at a big work table in the master bedroom.

In 1976, the City of Santa Clara decided that we were getting too big to operate from an apartment building, and we moved to the business park at 3046 Scott Blvd. in Santa Clara, where we stayed for three years. But this was when Silicon Valley was beginning to boom, and when we went to renew the lease in 1979, the cost had doubled.

I was then living in Santa Cruz, and discovered Scott and I could actually buy a commercially zoned house there for less money that the lease in Santa Clara. E-mu moved to 417 Broadway in Santa Cruz, and this was our home until the Emulator was well into production. Once again, our products were being assembled in a bedroom.

TO BE CONTINUED IN ONE WEEK